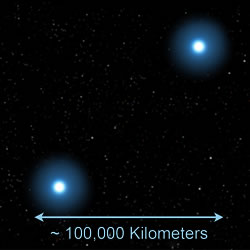

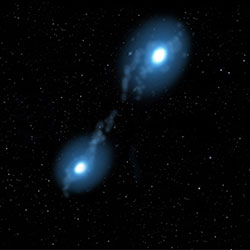

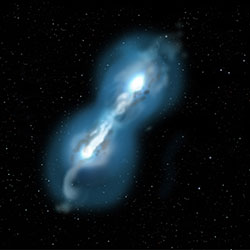

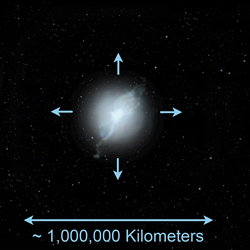

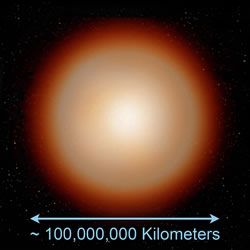

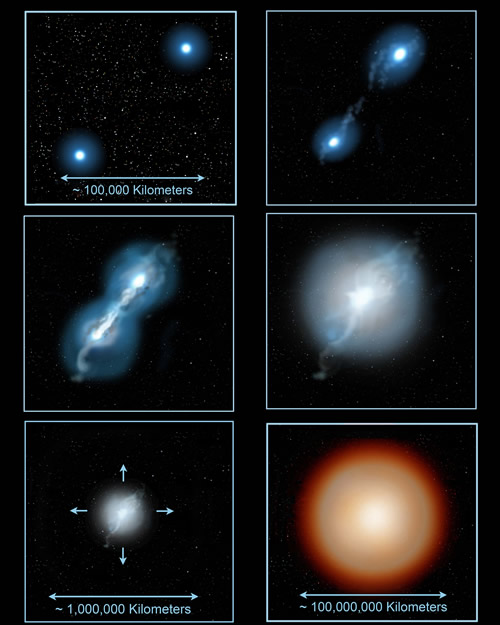

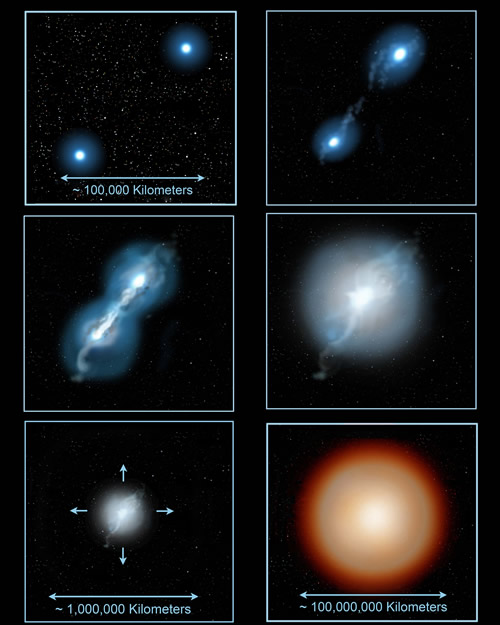

A pair of white dwarf stars in a close binary system are brought ever closer to each other, either by magnetic braking or gravitational wave emission, until one of the stars is disrupted and then merges with the other star. The gas becomes hot enough for nuclear reactions to take place. The energy produced causes the new merged star to expand and become a supergiant star, about a thousand times larger than the white dwarfs that formed it.

Gemini Artwork by Jon Lomberg, available at publication-quality resolution here.

For embargoed release at 9:30 AM (Pacific Time) on Tuesday, January 9, 2007

Science Contacts:

- Dr. Geoffrey C. Clayton

Louisiana State University,

Baton Rouge, LA

(225) 405-1617 (cell)

gclayton@fenway.phys.lsu.edu - Dr. Thomas R. Geballe

Gemini Observatory, Hilo, HI

(808) 974-2519 (desk)

(808) 345-6739 (cell)

tgeballe@gemini.edu

Media Contact:

- Peter Michaud

Gemini Observatory, Hilo HI, USA

(808) 974-2510 (desk)

(808) 937-0845 (cell)

pmichaud@gemini.edu

Astronomers have announced the discovery of huge quantities of an unusual variety of oxygen in two very rare types of stars. The finding suggests that the origin of these oddball stars may lie in the physics behind the mergers of white dwarf star pairs.

The unusual stars are known as hydrogen-deficient (HdC) and R Coronae Borealis (RCB) stars. Both types have almost no hydrogen - an element that makes up about 90% of most stars. Surprisingly, they contain up to a thousand times more of the isotope oxygen-18 than normal stars like our Sun. The discovery of abnormal quantities of oxygen-18 is based on near-infrared spectroscopic observations from the Gemini Near-Infrared Spectrograph (GNIRS) on the 8-meter Gemini-South telescope in Chile.

The findings were presented today at the 209th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle Washington by a team consisting of: Dr. Geoffrey C. Clayton (Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA), Dr. Thomas R. Geballe (Gemini Observatory, Hilo, HI), Dr. Falk Herwig (Keele University, UK) and Dr. Christopher Fryer (Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM), and Dr. Martin Asplund (Mount Stromlo Observatory, Australia).

Prompted by the discovery, the team roughly simulated the nuclear reactions that would occur during a merger of two types of white dwarfs, an idea originally proposed for the origin of RCB stars in 1984 by Prof. Ronald F. Webbink (University of Illinois). According to Clayton conditions had to be just right to yield the oxygen-18 observed in these stars. 'It's like the porridge in Goldilocks and the Three Bears. During the merger process, when nuclear reactions were taking place, the temperature was neither too hot, nor too cold, but just right for the production of large amounts of oxygen-18.'

One of the challenges in understanding these stars is how oxygen-18 can be formed from nitrogen in the star while maintaining more normal amounts of the isotope oxygen-16 made from the star's preexisting carbon. 'It's really the ratio of oxygen-18 to oxygen-16 that is important and in these stars that ratio is very lopsided. Although we need to do more precise modeling, it appears that the white dwarf merger theory might just allow this to occur,' said Clayton.

RCB stars are a small group of carbon-rich supergiants that undergo spectacular declines in brightness at irregular intervals, typically a few years in duration, before returning to their initial brightnesses. It is now thought that carbon grains intermittently condensing in the gas ejected by the star are responsible for dimming the star's light. On the other hand, the HdC stars, although resembling the RCB stars in their elemental abundances, do not eject gas and thus do not make dust or appear to vary in brightness.

An alternative theory to the merging of white dwarf pairs, originally proposed by Icko Iben (University of Illinois), is that oxygen-18 rich stars could be formed when a single star on the verge of becoming a white dwarf undergoes a final flash of thermonuclear burning near its surface. This inflates the star to supergiant size and cools off its outer atmosphere.

'This final-flash model is a tempting explanation because two stars known as V605 Aquilae and Sakurai's Object have recently been discovered going through the final flash phase where they resembled RCB stars in abundances, temperature, and brightness,' said team member Geballe. 'However, both of these stars are now known to have spent only a few years in this phase and given this extremely short period as cool supergiants this makes it unlikely that they can account for even the small number of RCB stars currently known in the Milky Way Galaxy.' These stars are so rare that a total of only 55 HdC and RCB stars have been identified in our galaxy.

'The properties and antics of these weird stars have been the subject of intense observation and discussion for generations of astronomers,' said Geballe. 'This discovery should help us pinpoint how the combination of two degenerate stars is different than the sum of their parts.'

Background Information:

The atom that we think of as oxygen has eight protons and eight neutrons and is called "oxygen-16" or 16O. This form of oxygen is by far the dominant form of oxygen everywhere throughout our Milky Way, it's found in interstellar clouds and distant stars, as well as on Earth and in the Sun. Two other stable forms of oxygen exist (isotopes), with one and two extra neutrons, known as oxygen-17 and oxygen-18 (17O and 18O). However, both of these isotopes are extremely rare. Our Earth, Sun, and most other stars and clouds in interstellar space studied to date have about 2700 times as much 16O as 17O and about 500 times as much 16O as 18O.

The unpredictable variability of RCB stars has made them popular targets for measurement by amateur astronomers and the source of much discussion by professionals seeking an explanation for their behavior. RCB star atmospheres are also extremely deficient in hydrogen, but very rich in carbon.

Two different evolutionary models have been suggested for the origin of RCB stars. Both theories invoke objects known as white dwarfs, the ultra-dense cores of previously normal stars like the Sun. They typically have masses about half that of the Sun, and their sizes are close to that of the Earth. In one model an RCB star is formed when two white dwarf stars merge. In the other model the RCB star is formed when a single star on the verge of becoming a white dwarf undergoes a final flash of thermonuclear burning near its surface, blowing the star up to supergiant size and cooling off its outer atmosphere.

In 1984 Prof. Ronald F. Webbink (University of Illinois) proposed that an RCB star is formed from the merger of a helium-rich white dwarf and a carbon/oxygen-rich white dwarf. He suggested that as the binary white dwarf coalesces into one object, the helium-white dwarf is disrupted, with part of it accreting onto the carbon/oxygen-white dwarf and undergoing thermonuclear "burning." The remainder forms an extended atmosphere around the object. Webbink proposed that this structure, a star with an He-burning outer shell in the center of a ~100 solar radii H-deficient envelope, is a RCB star.

Additionally, in 2002, Dr. Simon Jeffery (Armagh Observatory, Northern Ireland) and Dr. Hideyuki Saio (Tohoku University, Japan), suggested that a white dwarf pair merger could also account for the abundances of elements such as hydrogen, helium, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen seen in RCB stars. However, little is known about how the isotopes of these elements were created in these stars.

A pair of white dwarf stars in a close binary system are brought ever closer to each other, either by magnetic braking or gravitational wave emission, until one of the stars is disrupted and then merges with the other star. The gas becomes hot enough for nuclear reactions to take place. The energy produced causes the new merged star to expand and become a supergiant star, about a thousand times larger than the white dwarfs that formed it.

Gemini Artwork by Jon Lomberg, available at publication-quality resolution below.

Full-Resolution Images

A pair of white dwarf stars in a close binary system are brought ever closer to each other, either by magnetic braking or gravitational wave emission, until one of the stars is disrupted and then merges with the other star. The gas becomes hot enough for nuclear reactions to take place. The energy produced causes the new merged star to expand and become a supergiant star, about a thousand times larger than the white dwarfs that formed it.

Gemini Artwork by Jon Lomberg, available at publication-quality resolution here.

Algunas estrellas podrían responsabilizar de su singular anormalidad a sus Enanos Blancos Progenitores

Contactos Científicos:

- Dr. Geoffrey C. Clayton

Louisiana State University,

Baton Rouge, LA

(225) 405-1617 (celular)

gclayton@fenway.phys.lsu.edu - Dr. Thomas R. Geballe

Gemini Observatory, Hilo, HI

(808) 974-2519 (oficina)

(808) 345-6739 (celular)

tgeballe@gemini.edu

Contacto para Prensa:

- Peter Michaud

Gemini Observatory, Hilo HI, USA

(808) 974-2510 (oficina)

(808) 937-0845 (celular)

pmichaud@gemini.edu - Ma. Antonieta García

Gemini Observatory, La Serena, Chile

(56) 51- 205628 (oficina)

(56) 99182858 (celular)

La comunidad astronómica ha anunciado el descubrimiento de grandes cantidades de una inusual variedad de oxígeno en dos extraños tipos de estrellas. Este descubrimiento sugiere que el origen de estas singulares estrellas pudiera recaer en la física producida como consecuencia de las fusiones de pares de estrellas enananas blancas.

Estas estrellas poco comunes se conocen como hidrógeno – deficientes (HdC) y como estrellas R Coronae Borealis (RCB). Ambos tipos casi no tienen hidrógeno – un elemento que permite la existencia de cerca del 90% de la mayoría de las estrellas. Sorprendentemente, ellas contienen hasta mil veces más del oxígeno isotopo-18 que las estrellas normales como nuestro Sol. El descubrimiento de cantidades anormales de oxígeno 18 se basa en las observaciones espectroscópicas en el cercano infrarojo realizado con el instrumento del mismo nombre de Gemini (GNIRS) operativo en el telescopio de 8 metros de Gemini Sur, en Chile.

La noticia fue dada a conocer hoy en la reunión 209 del la Sociedad Astronómica Norteamericana en Seattle,, Estados Unidos por el equipo conformado por: Dr. Geoffrey C. Clayton (Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Los Angeles), Dr. Thomas R. Geballe (Gemini Observatory, Hilo, Hawaii), Dr. Falk Herwig (Keele University, Reino Unido) , el Dr. Christopher Fryer (Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, Nuevo México ), y el Dr. Martin Asplund (Mount Stromlo Observatory, Australia).

Motivados por el descubrimiento, el equipo simuló un bosquejo de las reacciones nucleares que ocurrirían durante una fusión de dos tipos de enanas blancas, una idea originalmente propuesta para el origen de las estrellas RCB en 1984 por el Profesor Ronald F. Webbink (Universidad de Illinois). Según Clayton, las condiciones tenían que ser muy precisas para ceder el oxígeno 18 obsevado en las estrellas. “ Es como el cuento de Ricitos de Oro y los Tres Osos. Durante el proceso de fusión, cuando se llevaron a cabo las reacciones nucleares, la temperatura no era ni muy caliente, ni muy fría, era la justa y precisa para la producción de grandes cantidades de oxígeno 18.”

Uno de los desafíos para comprender a estas estrellas es saber cómo el oxígeno 18 puede formarse a partir del nitrógeno en la estrella, mientras mantiene más cantidades normales de oxígeno isotopo - 16 el cual se forma a partir del carbón preexistente de la estrella.. “Lo que es realmente importante es el radio de oxígeno-18 a oxígeno 16, en estas estrellas el radio es muy ladeado. Aunque necesitamos hacer modelos más precisos , pareciera que la teoría de fusión de la enana blanca pudiera justo permitir que esto aconteciera,” mencionó Clayton.

Las estrellas RCB son un pequeño grupo de super gigantes, ricas en carbón, que atraviesan declinaciones espectaculares de brillo a intervalos irregulares, típicamente con un par de años de duración antes de regresar a su brillo inicial. Ahora se piensa que el carbón se granula intermitentemente, condensando el gas que es expulsado por la estrella responsable de la intensidad de brillo de la luz estelar. Por otro lado, las estrellas HdC, aunque se parecen a las RCB en sus abundancias elementales, no expulsan gas y por tanto, no producen polvo ni parecen variar en su intensidad de brillo.

Una teoría alternativa a la fusión del par de enanas blancas, originalmente propuesta por Icko Iben (Universidad de Illinois), es que las estrellas ricas en oxígeno -18 podrían formarse cuando una sóla estrella a punto de convertirse en una enana blanca atraviesa por un flash final de combustión termonuclear cerca de su superficie. Esto infla a la estrella a un tamaño super gigante y enfría su atmósfera exterior..

“Este modelo del flash final es una explicación tentativa ya que recientemente se han descubierto dos estrellas conocidas como V605 Objetos de Aquilae y Sakurai las que han sido captadas en la fase del último flash donde se parecen a las estrellas RCB en abundancia, temperatura y brillo,” señala Geballe, miembro del equipo. “En cualquier caso , ambas estrellas son ahora conocidas por haber pasado sólo un par de años en esta fase y haber tenido este período extremadamente corto como super gigantes frías , lo cual hace poco probable que puedan ser consideradas aunque sea por el reducido número de estrellas RCB que actualmente se conocen dentro de la Galaxia de la Vía Láctea.” Estas estrellas son tan poco frecuentes que apenas un total de 55 estrellas HdC y RCB se han identificado dentro de nuestra galaxia..

“Las propiedades de estas estrellas tan extrañas han sido objeto de intensas observaciones y discusiones para distintas generaciones de astrónomos,” asevera Geballe. “Este descubrimiento debería contribuir para que precisemos cómo dos estrellas en degeneración son diferentes a la suma de sus partes.”

Información Adicional

El átomo que nosotros conocemos como oxígeno posee ocho protones y ocho neutrones y se denomina “oxígeno -16” o 16O. Esta forma de oxígeno es , con seguridad, la forma más dominante de oxígeno en cualquier parte de nuestra Vía Láctea, se encuentra en nubes interestelares y en estrellas distantes, al igual que en la Tierra y en el Sol. Existen dos formas estables adicionales de oxígeno (isotopos), que tienen uno o dos neutrones extras , conocidos como oxígeno -17 y oxígeno -18 (17O y 18O). En todo caso, estos dos isotopos son extremadamente poco usuales. Nuestra Tierra, Sol y la mayoría de las otras estrellas y nubes en el espacio interestelar estudiadas hasta hoy, tienen alrededor de 2700 veces más tanto de 16O como de 17O y cerca de 500 veces más tanto de 16O como de 18O.

La impredecible variedad de estrellas RCB las ha convertido en blancos populares de medición por los astrónomos amateur y son un recurso de abundante discusión por parte de los profesionales que busacn una explicación a su comportamiento. Las atmósferas de las estrellas RCB son además extremadamente deficientes en hidrógeno, pero muy ricas en carbón.

Se han sugerido dos modelos diferentes de evolución para el origen de las estrellas RCB. Ambas teorías evocan objetos conocidos como enanas blancas, que son los núcleos ultra densos de estrellas anteriormente normales como nuestro Sol . Normalmente estas tienen masas cercanas a la mitad de la de nuestro Sol , y sus tamaños son similares a los de la Tierra.. En un modelo, una estrella RCB se formó cuando dos enanas blancas se fusionaron. En el otro modelo, la estrella RCB se formó cuando una sóla estrella a punto de convertirse en enana blanca atraviesa por un flash final de combustion thermonuclear cerca de su superficie, inflando la estrella a un tamaño de super gigante y enfriando su atmósfera externa.

En 1984 el Académico Ronald F. Webbink (Universidad de Illinois) propuso que una estrella RCB se formaba por la fusión de una enana blanca rica en helio y otra enana blanca rica en carbon/oxígeno. El sugirió que la enana blanca binaria se unía y conformaba un sólo objeto , la enana blanca de helio interrumpida, con parte de su acrecentamiento hacia la enana blanca de carbon/oxígeno sufriendo una reacción de “combustión” termonuclear .” El resto forma una atmósfera extendida alrededor del objeto. Webbink propuso que esta estructura , una estrella con una combustión externa de He en el centro de un ~100 radio solar H de envoltura deficiente, es una estrella RCB.

Adicionalmente, en el 2002, el Dr. Simon Jeffery (Armagh Observatory, Irlanda del Norte) y el Dr. Hideyuki Saio (Tohoku University, Japón), sugirió que un par de enanas blancas al fusionarse , también podría tener relación con la abundacia de elementos tales como el hidrógeno, helio, carbón, nitrógeno y oxígeno observados en la s etrellas RCB. En cualquier caso , se conoce poco acerca de cómo los isotopos de estos elementos se crearon en estas estrellas.